Feline misfortuneSeveral cats were taken to a Florida animal shelter with skin lesions on their ears, face and neck. Severe crusting and lichenification was observed on the pinna, with some of the cats unable to open their eyes due to the severity of the lesions. Skin scrapings were taken from 4 different cats revealing the following: Case contribution: Dr. Sarah Myers NCVP-Resident Notoedres cati, a contagious burrowing mite from the family Sarcoptidae. It infests cats, wild felids and other animals such as rabbits, foxes and dogs. Infestations with this mite produce alopecia, pruritus, crusting and self-excoriation. Usually, lesions are restricted to the auricles, head, face, neck, and shoulders.

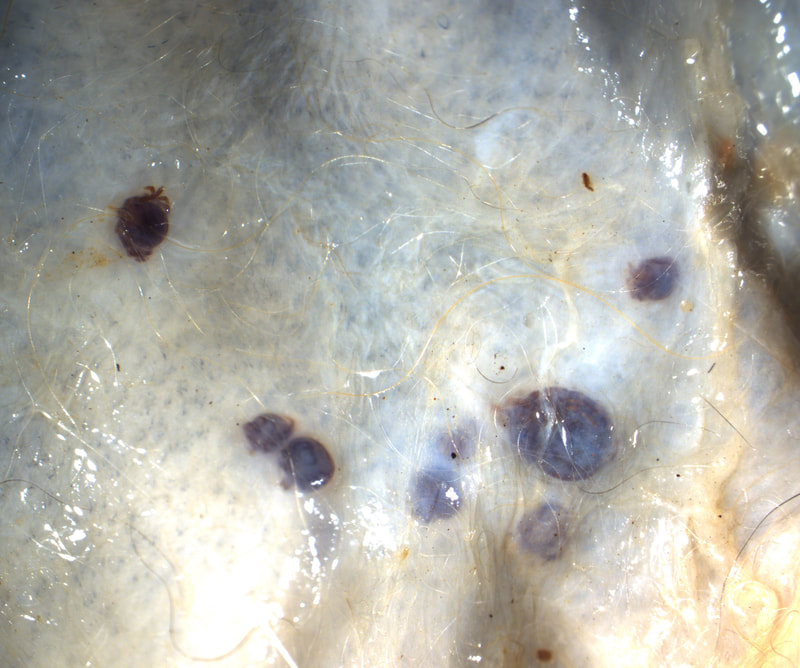

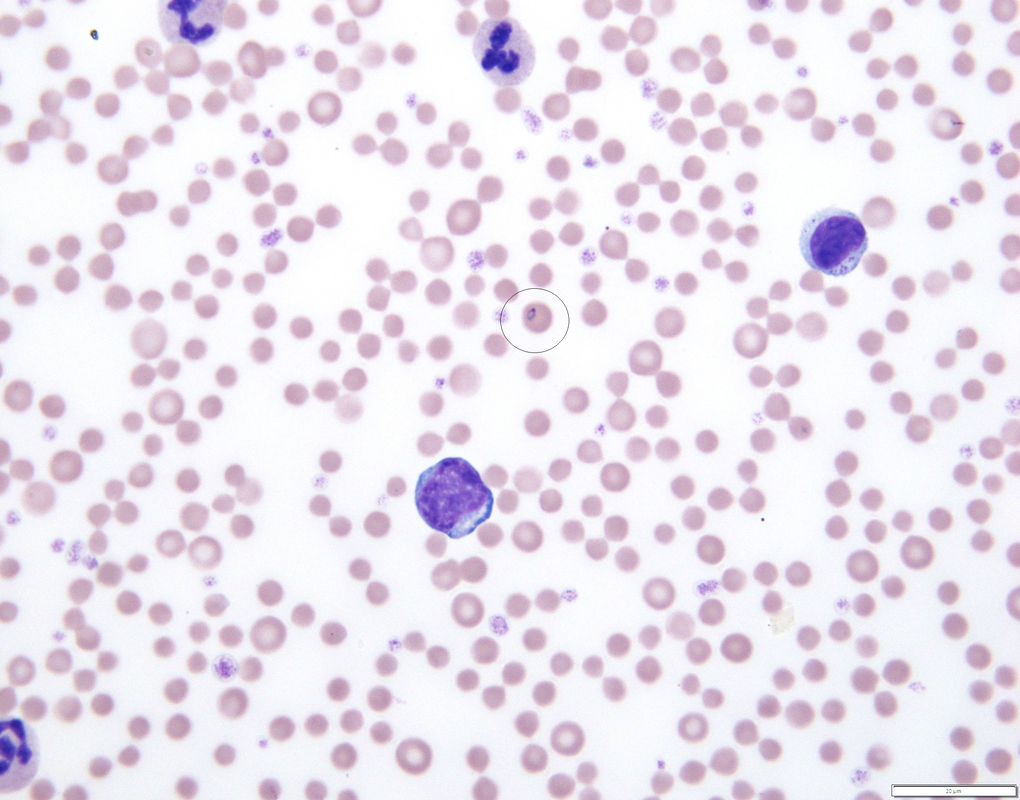

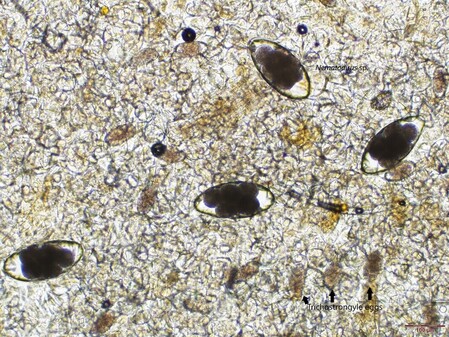

Differentiation from Sarcoptes scabiei can be done according to location of anus, in N. cati is dorsal (large arrow), while in S. scabei is in a terminal position. Additionally, N. cati dorsal spines are smaller and more rounded when compared to S. scabei (small arrows). Hitching a rideThe following tick was removed from a Gopher Tortoise from the Oklahoma Zoo, that was recently transported from Mexico. The engorged female tick measured approximately 1.5 cm in length (Image 1). Long palpi, scutal ornamentations not widely distributed, punctuations obvious, presence of eyes (Image 2); 4 hypostomal dentitions (image 3) and coxae IV with 2 short spurs (Image 4). Image 1: Engorged female tick Image 2: Long palpi, scutal ornamentations not widely distributed, punctuations obvious, presence of eyes Image 3: 4 hypostomal dentitions Image 4: Coxae IV with 2 short spurs Amblyomma sabanerae, adult female. These ticks have been reported from Mexico and Central America, infesting turtles of the genus Rhinoclemmys. Each adult tick can ingest more than 2 ml of blood. The serpent's parasitic perilA fecal sample from a 5-yeard-old male corn snake (Pantherophis guttatus) was submitted to the parasitology diagnostic lab at OADDL-Oklahoma for a general wellness examination. The fecal sample was soft, containing digested tissue and hair. Centrifugal flotation with Sheather’s sugar solution revealed the following: Image 1: Specimen 1 found on fecal float Image 2: Specimen 2 found on fecal float Mycoptes musculinus male and Hymenolepis diminuta egg. Mites of the family Myocoptidae are inhabitants of mice hair, while Hymenolepis diminuta is a cestode of rodents. Both are spurious parasites of the snake. The legs IV of the M. musculinus males are modified for clasping the female during copulation. These mites are commonly distributed on the dorsum or mice, feeding on debris without invading the skin. Transmission occurs by direct contact and some mice develop pruritus and alopecia. Himeloplis diminuta is a common cestode of rodents that requires a beetle as intermediate host. Infections are commonly subclinical. Not your usual case of formicationThe following images are from an approximately 2-year-old fox (Vulpes vulpes), necropsied at Oklahoma Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory. The fox was euthanized due to traumatic injury. This finding was incidental. (Images 1 and 2) Case contribution: Thank you to Ryan Carson-DVM class of 2026 and the AAVP student chapter at Oklahoma State University Image 1: Finding at necropsy Image 2: Microscopic view Subcutaneous Amblyomma americanum ticks (females, males, and nymphs). Ticks are obligate ectoparasites that spend part of their life attached to their hosts. They have mouthparts with chelicerae that pierce through the skin of the host. Attachment is facilitated by the tubular hypostome and a secreted cement or latex-like compound that attaches the tick to the host until the feeding is complete. Although most of the subcutaneous cases of subcutaneous ticks have described Ixodes spp., previous reports from Missouri and Arkansas have described the finding of intradermal infestations of red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) with Amblyomma americanum ticks. Other descriptions from other countries have mainly been from foxes, golden jackals, domestic and racoon dogs; and a single report also described the finding in a human. The reasons to explain the unusual location on these host are not clear yet, indications seem to suggest that immune response of canids may play a role. Bull all out of luckA 5-year-old Angus bull, was presented to the Veterinary Teaching Hospital at Oklahoma State University, with lethargy, coughing and wheezing of 3 weeks of duration. The following is an image of structures incidentally found on its blood smear (highlighted by circle). Case contribution: Thank you to Drs. Alys Harshbarger and Jim Meinkoth at Oklahoma State University for contributing to this case. Theileria orientalis is a tick transmitted protozoan parasite that infects erythrocytes and leukocytes. In the United States, native genotypes are usually non-pathogenic, however in the past few years an increase of T. orientalis genotype Ikeda that causes diseases, has been observed. Clinical signs associated with this intracellular parasite are anemia, jaundice and weakness. Haemaphysalis spp. ticks are the primary biological vector of T. orientalis and are considered essential for completion of the lifecycle. This case was tested by PCR and DNA sequencing and detected as T. orientalis genotype chitose. Parasitic EmbraceA 3-month old calf was submitted for necropsy to the Oklahoma Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory. The calf was found lying down 2 days before dying. During necropsy examination, the body presented moderate emaciation and anemia. The cecal and colonic contents were pasty with numerous parasites 1 to 1.5 cm long. (Image 1) Image 1: Parasites found in cecal and colonic contents Oesophagostomum sp.

Oesophagostomins are parasites of the large intestine of ruminants, swine and primates. The adults are 1 to 2 cm long and the eggs are 70 to 90 x 34 to 45 um. They are also called nodular worms because their larva can become encapsulated by a reactive inflammation in hypersensitive hosts. Acute inflammation may lead to diarrhea that can be fatal. This calf also had high numbers of Moniezia sp. eggs, and Nematodirus helvetianus, with the last one being pathogenic in young animals that have no acquired immunity. (Image 2) Image 2: Fecal centrifugation from small intestinal content |

Archives

July 2024

Have feedback on the cases or a special case you would like to share? Please email us ([email protected]). We will appropriately credit all submittors for any cases and photos provided.

|